Restoring Relationships for Lā Hoʻihoʻi Ea

Aloha mai kākou,

While our blog has been quiet this year, we have been busy. I am happy to be writing this from my apartment in Mānoa, where I now live. Previously at the University of Utah, on August 1, I officially join the faculty at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa in Ethnic Studies and Public Administration. Mahalo to the many, many friends and family who helped manifest this move home for me. I am thrilled to be back on Oʻahu after 20+ years, and to be able to continue my work on Nā Lei Poina ʻOle.

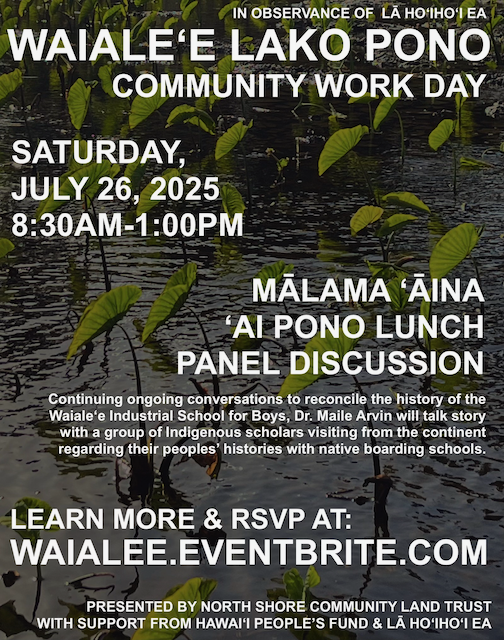

This weekend marks Lā Hoʻihoʻi Ea, Sovereignty Restoration Day. If you are on island, I would love to see you and catch up at any or all of these three events we have planned. Tomorrow, Saturday July 26 we will be at Waialeʻe 8:30-1pm. Sunday July 27, we will have a booth at Lā Hoʻihoʻi Ea Thomas Square, 9-5pm with a discussion panel at 10:30am. And Tuesday July 29, find us at UH Mānoa Hawaiian Studies for lunch and a share back presentation. You can find more details on each event on our social media pages, or below.

Me ke aloha

Maile

Ea: life, breath, and sovereignty.

Join us in uplifting the ea of Waialeʻe through mālama ʻāina and critical discussion. The ahupuaʻa of Waialeʻe is a Crown Land of Kauikeaouli, Kamehameha III, the Mōʻī who declared "Ua mau ke ea o ka ʻāina i ka pono (the sovereignty of the land endures because it is just)" upon the rightful restoration of sovereignty to the Hawaiian Kingdom following a brief British occupation in 1843. This date was thenceforth commemorated as Lā Hoʻihoʻi Ea (Sovereignty Restoration Day).

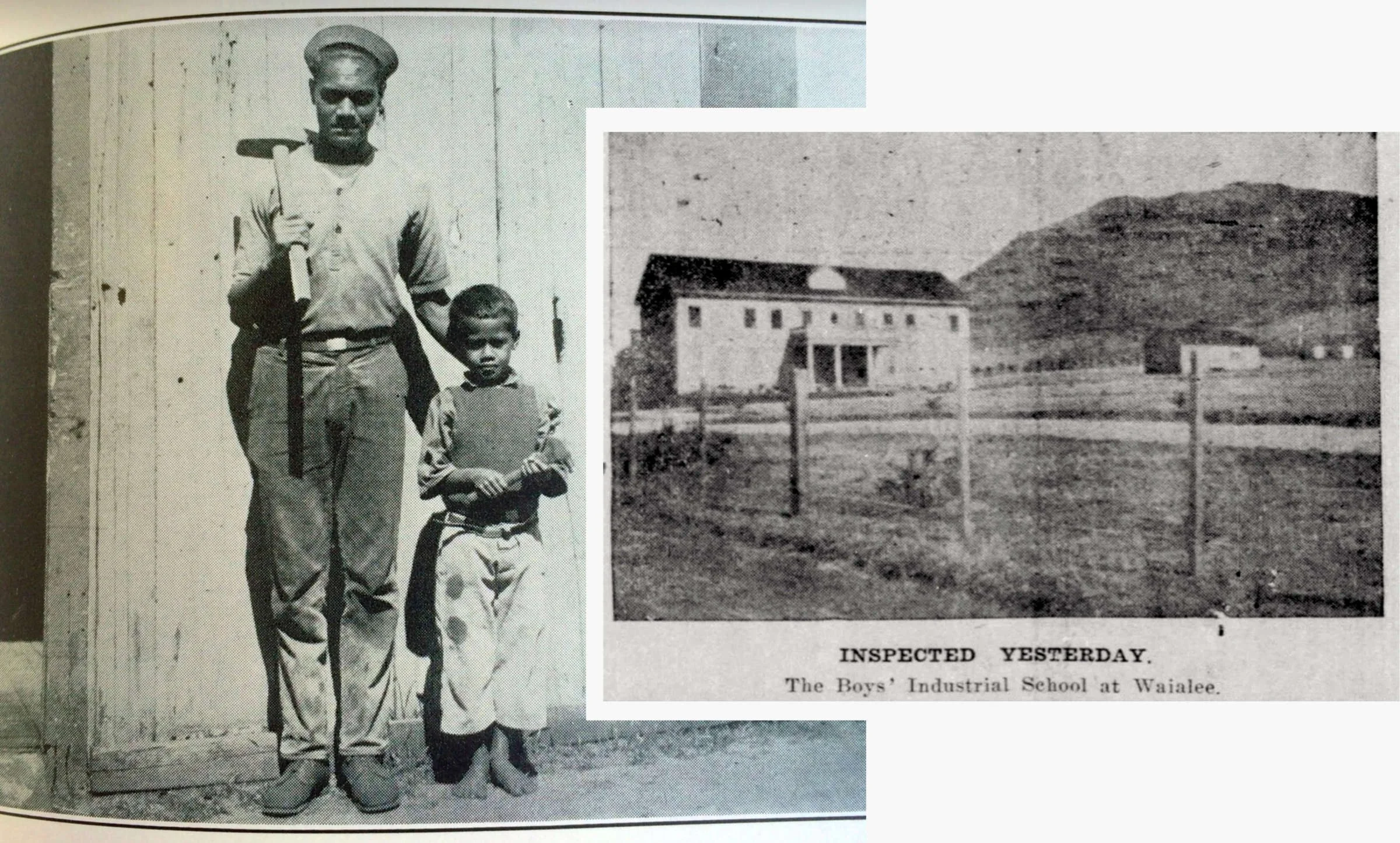

Ea has been disrupted in Waialeʻe through the eradication of native species and food systems, the displacement of Kānaka ʻŌiwi communities, and also the operation of the Waialeʻe Industrial School For Boys, which opened in 1903, shortly after the illegal annexation of the Hawaiian Kingdom in 1898. The boys' school criminalized and incarcerated predominantly Kānaka ʻŌiwi youth for minor "offenses," leading to unjustified trauma and indoctrination, rather than care and healing.

In an effort to uplift the ea of Waialeʻe and all those affected by the boys' school, during lunch we will learn from our Indigenous cousins' experiences with native American boarding schools and their efforts to heal from these schools' impacts.

Panelists will include:

Maile Arvin (Kanaka Maoli, University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa)

Derek Taira (Okinawan heritage, University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa)

Farina King (Diné, University of Oklahoma)

Caitlin Keliiaa (Yerington Paiute and Washoe, University of California, Santa Cruz)

Sarah Whitt (Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma, University of California, Irvine)

Kēhaulani Vaughn (Kanaka Maoli, University of California, Riverside)

Charles Sepulveda (Tongva and Acjachemen, University of California, Riverside)

As stewards of ʻāina, it is vital that we acknowledge, confront, and work to reconcile often uncomfortable histories which have taken place on these lands. We welcome you to join us in this journey to learn, grow, and ultimately heal from hurt that has been inflicted. E ea pū kākou a hoʻihoʻi i ke ea o Hawaiʻi! Let us all rise together to restore the life-giving breath of Hawaiʻi!

For more info and to RSVP, visit waialee.eventbrite.com

Sunday July 27

10:30am

Nā Lei Poina ʻOle booth at Lā Hoʻihoʻi Ea at Thomas Square

Continuing ongoing conversations about the history of the Waialeʻe Industrial School for Boys, we plan to talk story with a group of Indigenous scholars visiting from the continent. Join us!

Guests include:

Kawela Farrant, (Kanaka Maoli, North Shore Community Land Trust)

Maile Arvin (Kanaka Maoli, University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa)

Farina King (Diné, University of Oklahoma)

Caitlin Keliiaa (Yerington Paiute and Washoe, University of California, Santa Cruz)

Sarah Whitt (Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma, University of California, Irvine)

Kēhaulani Vaughn (Kanaka Maoli, University of California, Riverside)

Charles Sepulveda (Tongva and Acjachemen, University of California, Riverside)

Discussant: Makamae Sniffen (Kanaka Maoli, graduate student, University of Wisconsin)

Meet us at Kamakakuokalani Center for Hawaiian Studies room 207 next Tuesday 12-2!

For the past year, a group of faculty from several institutions including UH Mānoa have been collaborating around shared interests in histories of Indigenous boarding and industrial schools. Such institutions took Indigenous children from their families for years at a time. In doing so, they played key and painful roles in colonization across many different contexts, including Hawaiʻi. Join us for lunch and a talk story where scholars will share about their research and reflect on their year of working together. Guests include:

Maile Arvin (Kanaka Maoli, University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa)

Farina King (Diné, University of Oklahoma)

Caitlin Keliiaa (Yerington Paiute and Washoe, University of California, Santa Cruz)

Sarah Whitt (Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma, University of California, Irvine)

Kēhaulani Vaughn (Kanaka Maoli, University of California, Riverside)

Charles Sepulveda (Tongva and Acjachemen, University of California, Riverside)

Updates, with a full heart after connections at Waialeʻe

What a whirlwind time it has been for everyone. This blog post shares a few updates on recent events and a new publication.

What a whirlwind time it has been for everyone. This blog post shares a few updates on recent events and a new publication.

Mahalo e Waialeʻe

Three weeks ago, on Saturday Oct 19th, many of us gathered at Waialeʻe. We had a wonderful day sharing space and manaʻo with folks from the North Shore Community Land Trust, UH Sea Grant, KUA, Townscape, and most importantly, many community members who have long-standing pilina (relationships, ties) to Waialeʻe, or who were descendants of boys formerly incarcerated at the Industrial School for Boys. Townscape is working on a report summarizing the community input gathered that day, which we will share publicly soon. Mahalo to everyone who made the day possible and meaningful.

You can find photos and videos of the day on our Facebook and Instagram pages. The ʻāina of Waialeʻe is so beautiful, as is the work NSCLT is doing to restore the loʻi kalo (taro fields) and Kalou, the loko iʻa (fishpond) to lako pono (a state of abundance). You can join the work on the last Saturday of every month. The next one is Saturday, November 23rd. Find more details and sign-up here. Also be sure to check out a recent blog post by Eliana on a remarkable story of one boy who swam six miles out to sea to get away from the industrial school.

The Biden apology & NABS events in Hawaiʻi

A week after our time at Waialeʻe, President Biden apologized for the federal government’s role in federal Indian boarding schools. Though it may have come as a surprise to some, we have to understand the apology within at least two larger contexts. First, there has been a long history of advocacy for federal actions like this, by groups including the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition (NABS). Those efforts have born some fruit under the leadership of Department of Interior Secretary Deb Haaland, who spearheaded the release of two reports (one in 2022 and one in 2024) on federal involvement in “federal Indian boarding schools.” Several institutions in Hawaiʻi were included in this report, including the Waialeʻe Industrial School for Boys. Second, the apology was undeniably an effort to rally support to elect Kamala Harris. Even if she had been elected, we cannot know what the follow-through may or may not have been; but the uncertainty is even greater under a second Trump presidency.

I have written before about the similarities and differences between the industrial schools I study in Hawaiʻi and Native American boarding schools, and what the report gets wrong about Hawaiʻi. I will simply say here that the way that Native Hawaiians have been included in the federal reports on boarding schools and larger initiative leaves a lot to be desired. Many of you may have heard that there is a series of events hosted by the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition in Hilo and Kāneʻohe later this month. To be clear, I am not personally involved in those events; nor is our project Nā Lei Poina ʻOle involved. I support the overall cause of healing from institutional violence and intergenerational trauma - indeed, this is at the heart of this project - and greatly respect many who are participating in these events. I also think the November events are part of a top-down process that is not fully prepared to engage Native Hawaiian history with the care and time our communities deserve. How things proceed matter. This is lifetimes long, generations of healing work. I am interested in it for the long term, not just this election cycle.

New open-access article published

After many years in the works, my first academic article on the history of industrial schools in Hawaiʻi has been published, in open-access format here. Here is a sneak preview, and the full citation below.

In 1929, Dorothy Wu, a multiracial Native Hawaiian and Chinese teenager, suddenly found herself a ward of the Salvation Army Girls’ Home in Honolulu, Hawaiʻi, then a US territory. Until her institutionalization, Dorothy had worked as a maid in the home of Princess Abigail Campbell Kawānanakoa, a member of the aliʻi or ruling, royal class of the formerly independent Hawaiian Kingdom. To Dorothy’s bewilderment, the Princess abruptly fired Dorothy for “associating with boys,” and recommended her commitment to the Girls’ Home, where she could be “better cared for.” Dorothy found the Salvation Army matrons mean. She complained that they discriminated against “darker girls” like her. After six months, Dorothy ran away. Her escape soon landed her in juvenile court, which sentenced her to the Kawailoa Training School for Girls, a recently opened juvenile detention facility, where matrons worked to shape “wayward girls,” the majority of whom were Native Hawaiian and/or Asian, into “proper” and modern American women.

Arvin, Maile. “Replacing Native Hawaiian Kinship with Social Scientific Care: Settler Colonial Transinstitutionalization of Children in the Territory of Hawaiʻi.” Chapter. In Empire, Colonialism, and the Human Sciences: Troubling Encounters in the Americas and Pacific, edited by Adam Warren, Julia E. Rodriguez, and Stephen T. Casper, 123–52. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2024.

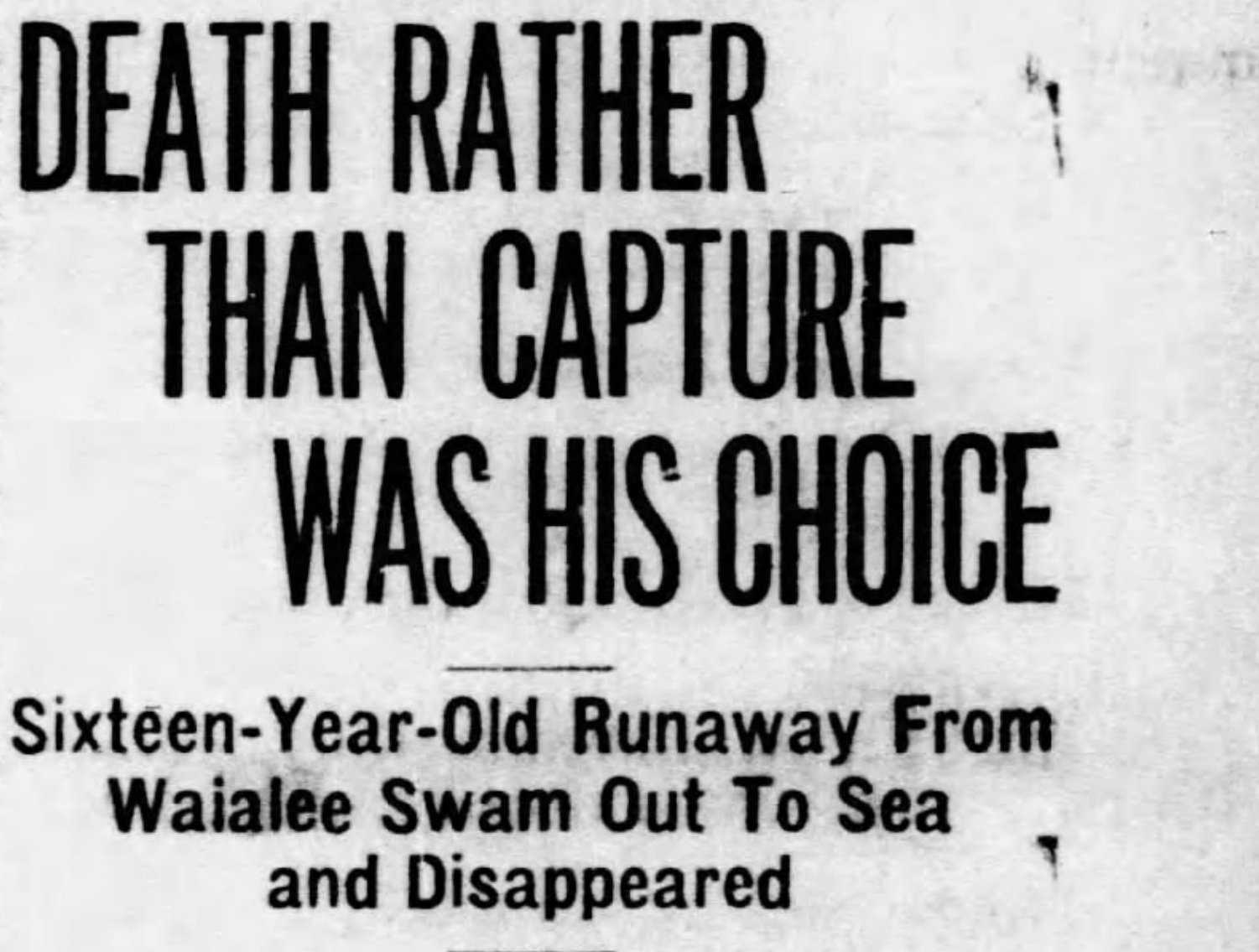

The Waialeʻe Runaway Who Swam Out to Sea

One morning in November 1918, Sam K. and his friend Willie C. ran away from the institution where they had been sentenced for the rest of their childhood for petty theft. As soon as the guards noticed they were missing, they began searching for them. Willie was caught just a few hundred feet from Waialua Beach, but Sam refused to give up. He plunged into the ocean.

One morning in November 1918, Sam K. and his friend Willie C. ran away from the institution where they had been sentenced for the rest of their childhood for petty theft. As soon as the guards noticed they were missing, they began searching for them. Willie was caught just a few hundred feet from Waialua Beach, but Sam refused to give up. He plunged into the ocean.

Photo of the beach at Waialeʻe. Photo by Eliana Massey.

Even though Sam was only 15 years old, he was a strong swimmer. He reached the first line of breakers before the guards could get a canoe into the water. Seeing the canoe coming after him, Sam swam farther out to sea. Soon, a crowd gathered on the beach to watch the race between Sam and the canoe. The guards chased him until they reached the reef, where the waves were crashing hard. At that point, they called a sampan (a small boat) to help find Sam, who had already swum nearly two miles.

Suddenly, Sam vanished. The sampan searched back and forth over the spot where he was last seen, but they couldn't find any sign of him. The crowd of onlookers grew worried, fearing Sam might have drowned from exhaustion or been attacked by a shark and notified the local police of his death.

The Honolulu Star Advertiser ran the headline, "Death Rather Than Capture Was His Choice: Sixteen-Year-Old Runaway From Waialee Swam Out To Sea.” But they spoke too soon. The search party on the sampan kept looking for Sam, and six miles from shore, they spotted him swimming calmly. When Sam saw the boat coming, he tried to escape by diving under the water again and again. On one dive, he made a mistake and surfaced too close to the sampan. A guard grabbed his hair and pulled him onto the boat, even as Sam fought to get free. Despite swimming for three hours, Sam showed no signs of being tired when they finally brought him back to shore. The Honolulu Star Advertiser ran a new headline: "Not Drowned, Just Swam Six Miles Out From Shore.”

Sam's bold escape probably made him a hero among the other boys at the institution. His story spread across the United States, appearing in newspapers in Washington, Tennessee, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, New York, and Arkansas, where he was compared to the famous swimmer Duke Kahanamoku.

In 1938, Sam’s story was reprinted in Hawaiʻi, 20 years after it first happened. That same year, the superintendent at the Waialeʻe Training School for Boys observed that their septic tank system was "inadequate," with waste draining directly into the ocean. He remarked, "I wouldn't think of swimming in the ocean off Waialeʻe." After a long day of work in the fields, many of the boys likely wished to cool off in the ocean, especially since the water pressure on the second floors of the dormitories was barely a trickle.

Sam’s escape is more than the thrilling story of a runaway; it highlights the harsh conditions at the Waialeʻe Training School for Boys, conditions that lasted long after he left. His daring swim out to sea, though ultimately unsuccessful, became a symbol of the desire for freedom.

E Hoʻomanaʻo Mau: Memorializing the Boys of Waialeʻe

Please join us on Saturday, October 19th, 9am-3pm at Waialeʻe Lako Pono for an event to gather community input on how to appropriately memorialize the history of the Waialeʻe Industrial School for Boys (1903-1950). RSVP here, and please share with anyone who has ties to or interest in the history of the Waialeʻe Industrial School for Boys.

New logo & other updates on our website

A hala and ʻilima lei for beloved keiki never forgotten

If you have visited our website or social media accounts lately, you may have noticed some new features. We are especially excited to share a new logo for our project!

Designed by Kanaka Maoli artist and scholar Makamae Sniffen, embodies the ʻōlelo noʻeau “He lei poina ʻole ke keiki,” from which we take our project name. It features an image of a child with their arms clasped around a parent, as well as a flower lei of hala and ʻilima. These pua were traditionally associated with Waialeʻe, the site of the boys’ industrial school, as documented by Kawela Farrant. Hala further signifies moments of great transition, including passing away, while ʻilima is the flower symbolizing the island of Oʻahu. The keiki faces the audience - reminding us of their resilience, while the makua - although more transparent and facing away - reminds us that, despite their separation, they are still there and ready to care for and carry their keiki. The title font evokes the art deco style of the Territorial era of Hawaiʻi, when the institutions we study operated.

We also have a lot of new resources on our website.

Timeline — Created by our student researcher Callie Avondet on Tableau, this interactive timeline allows you to see an overview of major events in the history of juvenile detention in Hawaiʻi. You can also select specific institutions like the Waialeʻe Training School for Boys or the Kawailoa Training School for Girls to focus on those specific histories.

Zines — We have two zines (mini-magazines) to share! One is about the Waialeʻe Training School for Boys — and was created by student researcher Eliana Massey. And one is about the Kawailoa Training School for Girls, created by Callie Avondet. We passed out hard copies of these at some of our events on Oʻahu over the summer, but be sure to check out the online versions as they have a few extra pages. We have also updated this page to include a photo for each school site we study. As our work continues, we hope to add more zines and resources for each site.

Storymap — This interactive map shows the locations of the institutions we study, all located on Oʻahu. This has been on our website for a while but we moved it front and center on our Home page.

Resources — Also included in our zines, this page lists a number of resources related to mental health and coping with trauma, especially within Native Hawaiian communities.

Contact — On our contact page, we address families who may have had an ancestor at one of the institutions we study. We are actively compiling a working list of names of children who were held at the schools — from 1865 through 1963. We will not make this list public online but can look up family names or share the list in person as requested.

As our researchers gear up for a new semester, we extend our deepest mahalo to everyone who continues to support our work. A special thanks to Callie Avondet, who has been a central member of our student researcher team, as she leaves us to go on to graduate school. Stay tuned for more updates over the next few months.

Join us at Lā Hoʻihoʻi Ea, Sunday July 28th, Thomas Square

Join us at Lā Hoʻihoʻi Ea in Thomas Square, Sunday July 28!

Our team has been busy this summer - researching at the Hawaiʻi State Archives and elsewhere, building relationships with community partners, and searching for ʻohana with direct ties to the Waialeʻe Training School. We plan to share more updates from our summer soon. In the meantime, please join us in celebrating Lā Hoʻihoʻi Ea (Restoration Day), a commemoration of the restoration of Hawaiian sovereignty in 1843 after the nation had been seized by a rogue British naval captain. It is an important holiday that celebrates- and practices - Hawaiian ea (life, breath, independence). We will have a booth, in partnership with the North Shore Community Land Trust. Our intention is to talk story with anyone who wants to, to share more about the history of the Waialeʻe Training School for Boys. So please come by Thomas Square in Honolulu tomorrow July 28th. We will be there all day - 10am to 6pm.

June Events

Join us at Waiale’e on June 18 and June 29.

Oʻahu friends, I will be sharing about my research on kula hoʻopololei (reformatory schools) at Waialeʻe twice this month - on Tuesday June 18, 5-7pm, and Saturday, June 29, 12-2pm, after the North Shore Community Land Trust's regular workday from 9-12. Please join if available and interested, or share with others who might be. Free and there will be food!

Meet at Waialeʻe Lako Pono, at Waialeʻe, off Dairy Rd (ma kai side near pink roof barn).

Link to Google Map Directions

Our team is also tentatively planning a longer event at Waialeʻe on Saturday July 27th, and potentially a booth at Lā Hoʻihoʻi Eā in Thomas Square on Sunday July 28th. Stay tuned for more details. We are excited to connect with folks and talk story!

Regenerating Life & Land at Waialeʻe

In November 1915, Hawaiian newspapers reported on a haunaele nui (large riot) at the Waialeʻe Industrial School for Boys, located in a rural area on the North Shore of Oʻahu. After assaulting a teacher, fifty-four children escaped into the nearby mountains. Pursued by teachers on horseback, the majority were returned to the institution at gunpoint. The boys involved explained that the cause of this incident was hunger: they were not being fed enough.

Clipping of the front page of Kā Nūpepa Kūʻokoʻa, Novemaba (November) 26, 1915. The headline of the first story is “Ulu He Haunaele Nui Ma Ke Kula Hoʻopololei Ma Waialeʻe” (A large riot springs up at the reformatory school at Waialeʻe). Clipped from Papakilo.

In November 1915, Hawaiian newspapers reported on a haunaele nui (large riot) at the Waialeʻe Industrial School for Boys, located in a rural area on the North Shore of Oʻahu. After assaulting a teacher, fifty-four children escaped into the nearby mountains. Pursued by teachers on horseback, the majority were returned to the institution at gunpoint. The boys involved explained that the cause of this incident was hunger: they were not being fed enough.

Opened in 1903, the Waialeʻe Industrial School was part of a larger government-run system of institutions that incarcerated children and adults in the Territory of Hawaiʻi. The same white settlers who overthrew the Hawaiian Kingdom in 1893 became the leaders of the new Territorial government in 1900. Yet white people remained a small minority in Hawaiʻi, and thus the government enacted a number of measures to repress Native Hawaiian language, culture, religion and political loyalty to the former Kingdom government. The Industrial School at Waialeʻe remained open at the site until 1950.

In Hawaiian, the word for land is ʻāina, which literally means “that which feeds.” When we think about hungry children running away from the Waialeʻe Industrial School in 1915, we are also reminded of the beauty of what is happening on that same land now. Today, our partner non-profit organization, the North Shore Community Land Trust, works at the site to restore loʻi kalo (areas for growing taro, a traditionally important staple food) and a freshwater fishpond.

This summer, our research team will be on Oʻahu conducting further research and looking to connect with community around the history of the Boys’ School at Waialeʻe. We are very grateful to have garnered two grants to support this work. The first, which is being directly granted to the North Shore Community Land Trust, is a National Endowment of the Humanities (NEH) Chair’s grant that was recently made available to communities and sites named in the Department of Interior’s Federal Indian Boarding School Investigative Report. This grant will allow us to conduct community meetings at Waialeʻe to share more about the history of the Boys’ school, discuss how this history should be memorialized, and create digital story maps that can explain some of the history of the Boys’ school while connecting to the site as it stands today.

The second is an American Council of Learned Societies (ACLS) Digital Justice Seed Grant, which will allow us to continue this momentum and create the foundations of a digital resource about the history of industrial schools in Hawaiʻi — including the Boys’ School but also the other sites our researchers are interested in (at Keoneʻula, Mōʻiliʻili, Waimano, and Kawailoa). We plan to use Mukurtu, a content management site platform that was designed with Indigenous communities in mind. The site allows for different levels of access to follow and enact Indigenous cultural protocols around sharing cultural heritage and history. We hope to provide interpretation of this history that situates these institutions within a longer history and future of the lands they occupied.

These lands, where the industrial schools starved children, were always meant to feed us. The vision we have for our work, put simply, is to make these places sites that feed Native Hawaiians – literally, culturally, and spiritually. Overall, what we propose is meant to offer space and time for the communities impacted most by the history of these schools to process, grieve, and heal. That healing will be a long-term, collective process. But we know that bringing more people to these sites and allowing them to walk, talk, and learn on the land will feed us all in many ways, and help us ensure that the children kept at the industrial schools are not forgotten.

Please stay tuned for several opportunities to connect with our team on Oʻahu in June and July. We are planning an informational meeting in mid-June - to share more about us and our work; and a talk story event after the community work day at Waialeʻe on Saturday, June 29th; along with a couple of other possibilities still in the works! We will update our brand new social media accounts when we have more details — see the links to our Instagram and Facebook pages below.

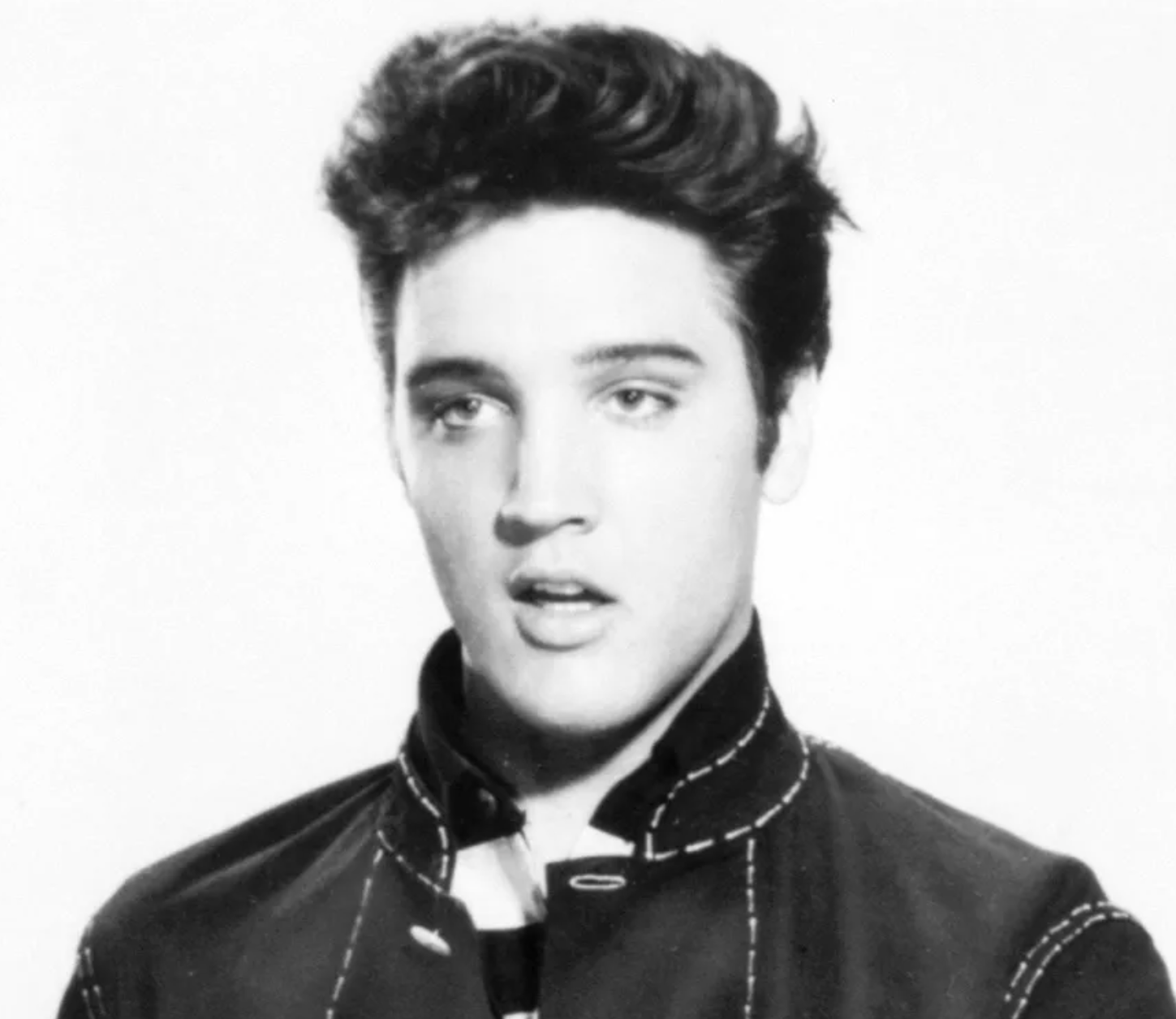

We, the Women: Public Perceptions of Juvenile Delinquency in the 1950s

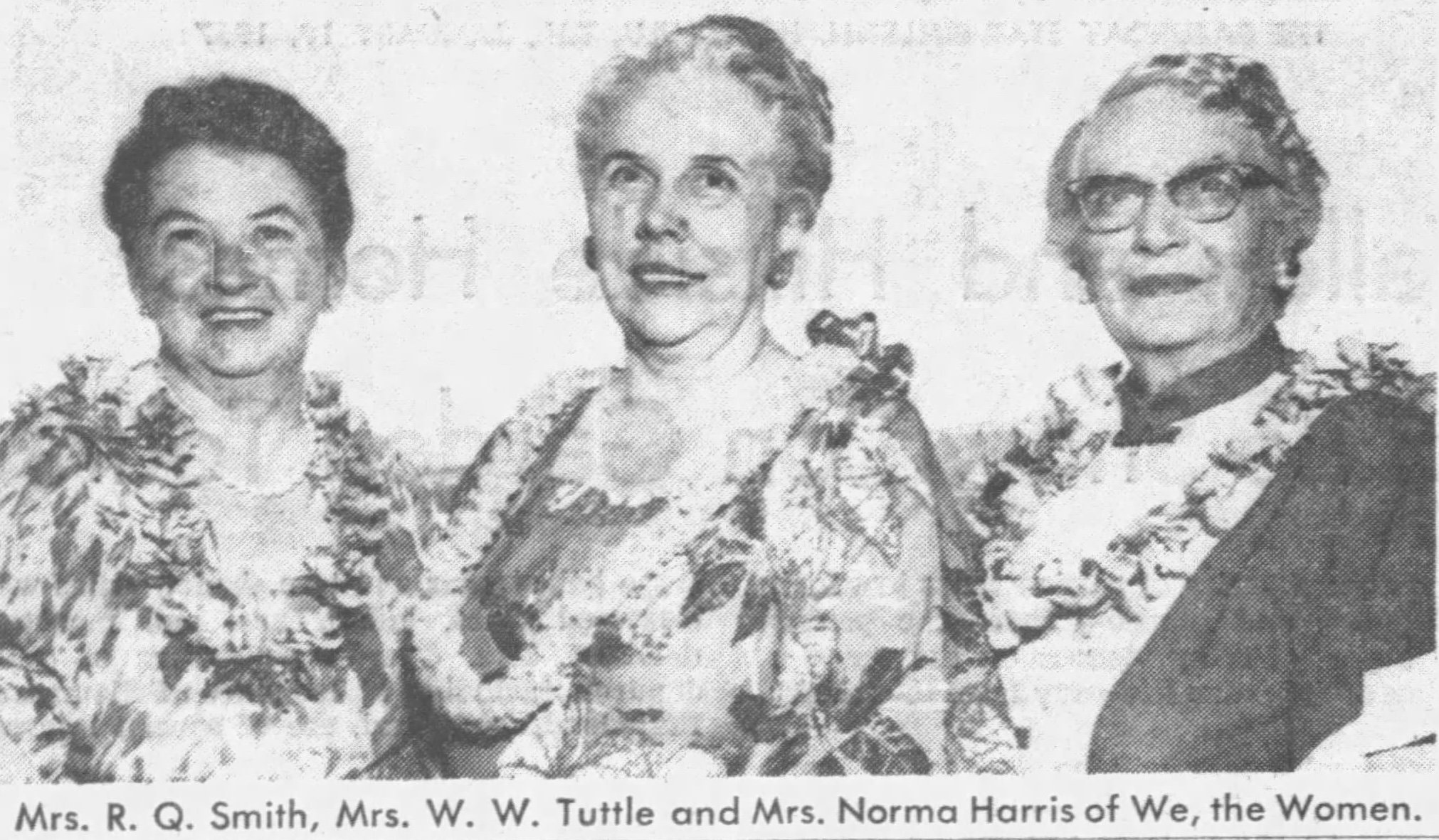

Despite his popularity, Elvis can’t explain all the public concern about juvenile delinquency in Hawaiʻi during 1957. Organizations such as We, the Women had brought juvenile delinquency to the forefront of public awareness since the early 1950s. We, the Women was a conservative women’s group in Hawaiʻi born to protest an impending public utilities worker strike in 1946.

In 1957, Hawaiʻi residents hotly debated Elvis Presley’s dance moves. The Honolulu Star-Bulletin reported “receiving far more letters for and against Elvis Presley than we can possibly publish.”[1] Eunice Kiyuna, a 13 year old living on Hawaiʻi was one of the few who successfully got her letter in the paper, arguing that she “didn’t see anything wrong with his singing or his style of shaking.”[2]

The public also critiqued other aspects of Elvis. In addition to his dancing, Elvis’ “haircut that doesn’t look like a haircut" garnered public attention.[3] The length and volume all marked his unique hairstyle and brand.

Some people, however, associated Elvis’ brand, including his haircut, with juvenile delinquency. Rather, teenage boys having such an “extreme coiffure” was a “badge of delinquency” that would almost certainly signify the boy would soon be following Elvis’ footsteps towards arrests.

Despite his popularity, Elvis can’t explain all the public concern about juvenile delinquency in Hawaiʻi during 1957. Organizations such as We, the Women had brought juvenile delinquency to the forefront of public awareness since the early 1950s.

We, the Women was a conservative women’s group in Hawaiʻi born to protest an impending public utilities worker strike in 1946. They claimed to represent “thousands of other women in the Territory,” and reported 300 women showing up to their meeting that approved a letter to the governor asking him questions such as, “What do you plan to do to make it forever impossible for a minority group to put its selfish interest above the general welfare to the extreme extent of shutting off utilities?” and pushing back on the lack of prosecutions against previous strikers.[4] When August 1st came around, the day the strike was planned to begin, the Honolulu Star-Bulletin instead circulated Letters from Readers about how to prevent “the threatened and perhaps still pending strike” from happening and praising We, the Women for organizing.[5]

“‘We, the Women of Hawaii’ (God bless ‘em), have now arrived.”

In the early 1950s, We, the Women organized around legislative changes. They hosted luncheons to discuss issues such as fluoridating water, sales taxes, and juvenile delinquency. We, the Women, a juvenile court judge, and other officials believed that the best way to prevent juvenile delinquency was through education reform. We, the Women supported a platform that increased the number of remedial education teachers, vocational education classes, and “required courses in family living in intermediate and high school levels.”[6]

Their early efforts failed to curb juvenile delinquency and when We, the Women took up juvenile delinquency again in 1957, they prioritized community action rather than pressure on the legislature. The agenda consisted of three main components: “Cause and treatment of youthful crime,” “Study of existing criminal code and penalties for ‘offenses against the person’ and offenses against property,” and “The rights of the citizen to protect himself and his property.” This agenda marked a stark difference from their focus on prevention in the early 1950s. Instead, We, the Women prioritized understanding the law and protecting themselves and their property. Their self-interest in juvenile delinquency rather than public or youth interest took precedence by 1957.

“Federal officials testify on juvenile delinquency. It’s a nonpartisan problem. Each party is convinced the other one proves what happens to juvenile delinquents.”

Juvenile delinquency was in the forefront of public concern and We, the Women wanted to expand the number of people and groups involved in tackling it. In addition to the eight women’s groups already working with them, We, the Women invited over 200 other groups on Oʻahu to join their task force.[7] Not only did We, the Women’s status and recognition on the island help bring attention to juvenile delinquency, it was already a large enough issue to garner so much public support and attention.

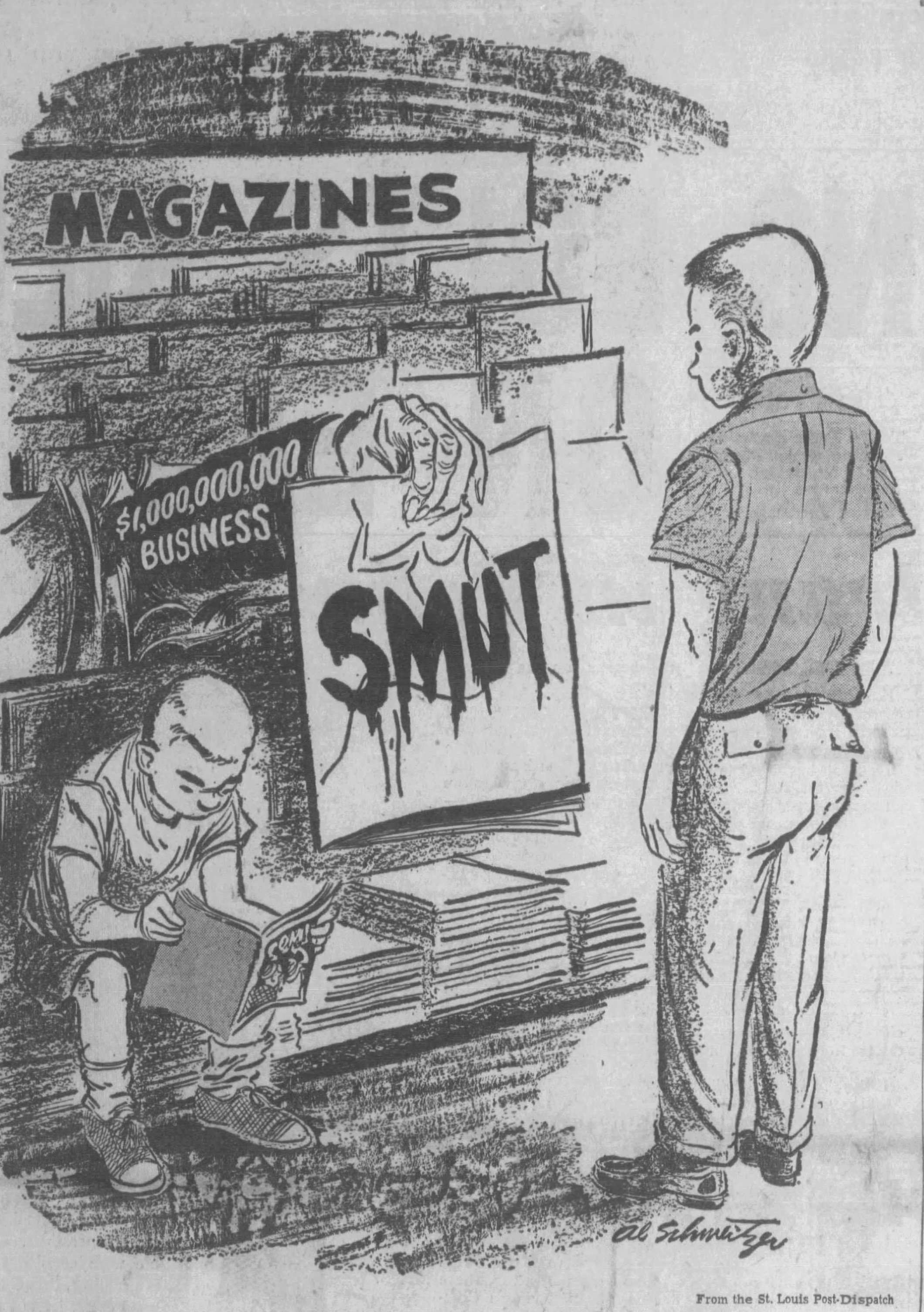

By late 1957, We, the Women’s campaign created the Community Crime Council. Strangely, the first 6 person board did not include a representative from We, the Women, but largely adopted their proposed agenda. Mrs. Kellerman, of We, the Women, credited as a key force in creating the council, and We, the Women was likely one organization who partnered with the council from the beginning. Council members spoke at public events and conducted community research to raise public consciousness about juvenile delinquency and what they believed were its causes, such as “smut” literature.[8]

We, the Women’s work throughout the 1950s reflected and amplified concerns about juvenile delinquency by organizing people against the perceived threat. Examining their role and public conversations around Elvis Presley help us understand how threatening the public found juvenile delinquency, and commonplace its causes.

[1] Eunice Kiyuna, “Letters from Readers,” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, February 12, 1957.

[2] Kiyuna.

[3] Elvis Presley as quoted in Wayne Harada, “Music,” Honolulu Advertiser, November 17, 1957.

[4] Mona H. Holmes et al., “Why No Action, Stainback Asked,” Honolulu Advertiser, July 25, 1946, https://www.newspapers.com/image/259267916/?terms=%22We%2C%20the%20Women%22&match=1.

[5] ONE OF THEM, “Letters from Readers,” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, August 1, 1946, https://www.newspapers.com/image/258514487/?terms=Public%20utilities%20strike&match=1.

[6] “Women Indorse Program on Juvenile Delinquency,” The Honolulu Advertiser, March 12, 1953.

[7] Fletcher Knebel, “Potomac Fever,” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, November 27, 1953, https://www.newspapers.com/image/258863501/?match=1&terms=%22Potomac%20Fever%22%20.

[8] “200 Clubs Asked to Join Juvenile Delinquency Fight,” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, September 25, 1957.

[9]“City Crime Rate Increases Among Those Under 25,” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, November 16, 1957; “Council Formed to Fight Crime Among Juveniles,” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, October 31, 1957; “Smut Literature Available to Teenagers in Hawaii,” The Honolulu Advertiser, August 30, 1959.

Moʻolelo as Resistance at Kawailoa Industrial School for Girls

The teenage girls who were incarcerated at Kawailoa Industrial School were not too different from teenage girls today. They enjoyed watching action-packed movies, staying up to date on the love lives of their favorite celebrities, and talking about their crushes and “first times.” In 1939, adventure stood out as the favorite movie genre among the majority (57%) of girls living at Kawailoa Industrial School, as indicated by a survey with 65 responses.

A long-distance view of Kawailoa Industrial School for Girls from a 1940’s institutional scrapbook. Digitally colorized.

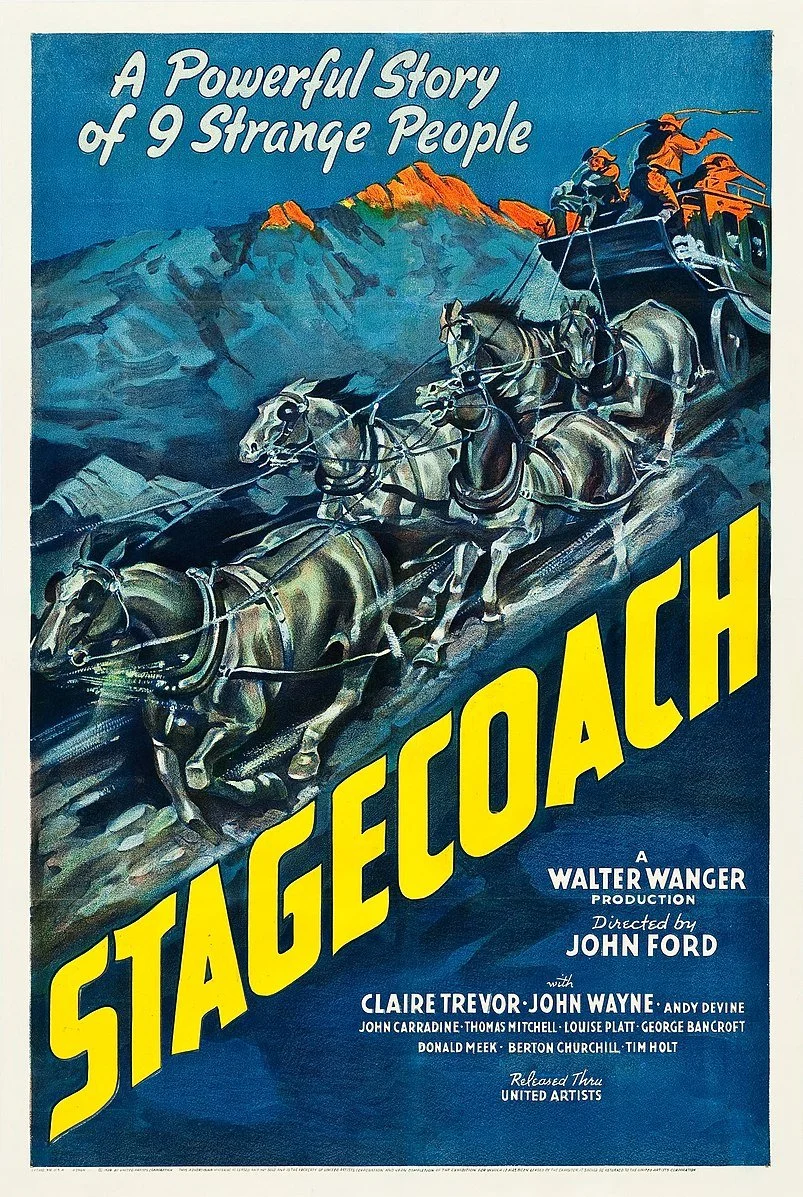

The teenage girls who were incarcerated at Kawailoa Industrial School were not too different from teenage girls today. They enjoyed watching action-packed movies, staying up to date on the love lives of their favorite celebrities, and talking about their crushes and “first times.” In 1939, adventure stood out as the favorite movie genre among the majority (57%) of girls living at Kawailoa Industrial School, as indicated by a survey with 65 responses. The 1939 cinematic landscape included The Wizard of Oz, which continues to enchant viewers with its timeless melody "Somewhere Over the Rainbow," Stagecoach, starring John Wayne in his breakthrough role, and The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes, which was the last Sherlock Holmes film set in the Victorian period. Out of the Western, mystery, and crime subgenres, the girls preferred westerns and mysteries.

While it is difficult to know exactly how incarceration at Kawailoa Industrial School affected the girls' preferences, we can speculate that the boredom and drudgery of confinement might have fed their love for adventure films.

Softening into fictional worlds where “troubles melt like lemon drops” likely offered some solace to girls who missed their loved ones.

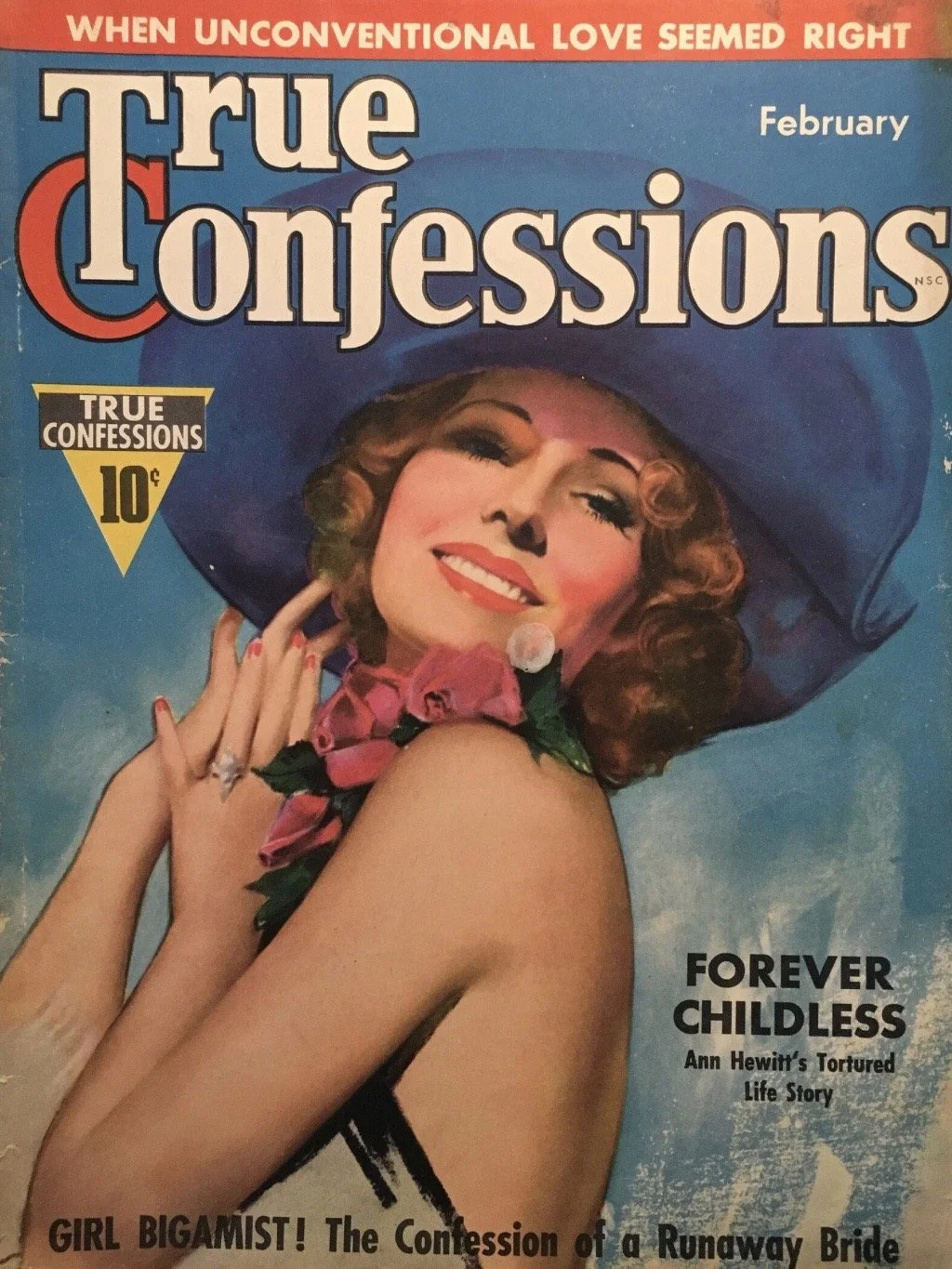

The previously mentioned 1939 survey also found that romance was the favorite written genre of the largest percentage of girls (48%) living at Kawailoa Industrial School. In particular, the girls liked reading the popular magazines True Confessions and Screen Stories. These magazines probably offered not just entertainment but also a feeling of normalcy for teenage girls, many of whom were 18 or older, who were deprived of normal opportunities to explore romance and sexuality. At least some girls also viewed magazines like these as sources of sexual information. When asked about their sexual education sources, 13% of 36 respondents mentioned books and magazines.

Another 20% of girls at Kawailoa Industrial School in 1939 stated that they had no sexual education. Determining whether social taboos surrounding sex may have influenced this response is challenging. However, it is clear that many girls at Kawailoa Industrial School were lacking substantial information regarding sex and likely held inaccurate beliefs.

While many other girls in Hawaiʻi during this era also received inadequate sexual education, they were fortunate to at least have access to guidance from their mothers and aunties. In contrast, girls at Kawailoa Industrial School had very limited opportunities to interact with their mothers and aunties. This exacerbated their sexual vulnerability.

Girls at Kawailoa Industrial School turned to each other for sexual information, with 18% of survey respondents indicating that their female friends were their first sources of sexual knowledge.

“It is common practice for girls, who have run away and have been apprehended, to be returned to their respective cottages where they entertain the other girls with tales of their escapades and conquests while on “leave.” Their sex experiences are the choice bits of entertainment.”

While the author of the article quoted above included these details as evidence of the supposed inadequacy of moral training at Kawailoa Industrial School, these habits can also be interpreted as a strategy employed by the teenage girls to address their lack of sexual education. The storytelling sessions following escapes allowed girls to share information with each other about their bodies and the world beyond the confines of the institution.

While escapes posed a direct challenge to the institution's control, “talking story" after recapture might be seen as an equally significant form of resistance.

Moreover, these talk story sessions likely motivated further escapes which surely led to more storytelling gatherings, thus reinforcing a unique moʻolelo-based cycle of resistance.

Mo’olelo, which is often translated into English as “story,” is composed of the words moʻo (a series of events such as the repeated shedding of a lizard’s skin) and ʻōlelo (language or spoken words).

Moʻo is a particularly helpful word for describing these post-escape (and pre-new-escapes!) talk story gatherings. Given the sheer quantity and frequency of escapes, these moʻolelo-sharing events were likely repeated on a weekly basis.

Photo by Egor Kamelev

The “tales” of their friends’ “escapades and conquests” undoubtedly brought much pleasure to the girls’ adventure-loving hearts. Unfortunately, this practice also touches on one of the darkest sides of life for girls incarcerated at Kawailoa Industrial School.

“The girls who work as prostitutes and are sent to the school tell other girls the names and addresses of solicitors who are always willing to harbor an escaped girl. It is not incidental that the girls are enlisted into the ranks of prostitution for the privilege of staying out of the hands of the police.”

This quotation offers a small glimpse into the difficult decisions girls faced as a result of the carceral system. Freedom remained elusive regardless of what choices a girl made under these circumstances.

While the pleasure of watching, reading, sharing, and listening to stories did not negate this reality, it empowered these girls to experiment with freedom.

A reflection on our summer 2023 visit to Oʻahu

The marks of the physical and ideological structures of the colonial institutionalization of children in Hawaiʻi are still visible and textural like the wet shadow in the sand. For example, when we walked through the trees at Waialeʻe, I recognized the concrete base of the windmill from historical photographs of the Boy’s Industrial School at Waialeʻe.

As I stood on the beach with the waves washing over my feet, my mind became quiet and my movements slowed. When a wave recedes, the sand is dark and heavy with the impression of where the wave washed over. This shadow of the wave has a life of its own. It echoes the wave that created it by moving forward as if pulled toward the ocean. This phenomenon hugged my attention like a net. The mark is a memory, a shadow in the sand. I marveled at the way this phenomenon connected to the reason I was in Hawaiʻi.

According to some neuroscience studies, every time you remember a past experience, your mind/body changes in ways that alter future recall (Bridges and Paller 2012). The next time you remember that event, you might not recall the original event but the most recent memory (Paul 2012). In other words, every time I recall my experience on the beach, my mind/body might create a memory of a memory of a memory of the event. This succession or moʻo occurs not just over an individual lifetime, but also over many lifetimes. Like the shore, the bodies of the descendents of institutionalized children might also be dark and heavy with the fading memories of the trauma of incarceration.

The marks of the physical and ideological structures of the colonial institutionalization of children in Hawaiʻi are still visible and textural like the wet shadow in the sand. For example, when we walked through the trees at Waialeʻe, I recognized the concrete base of the windmill from historical photographs of the Boy’s Industrial School at Waialeʻe. Kawela Farrant also pointed out numbers carved into the concrete of a structure used by the Boy’s Industrial School at Waialeʻe. Kawela suggested that the numbers might be inmate numbers assigned to children. In particular, I was struck by a carving which read “591-Kid.” Later, in the Hawaiʻi State archives, I found a roster of children held at the Boy’s Industrial School at Waialeʻe with a column of 3-digit inmate numbers. This roster also included information about why each child was sent there. For example, a 13 year-old Native Hawaiian child was committed for “no less than 2 years” for being “an idle and dissolute child.” Another 12 year-old Native Hawaiian child was committed for “no less than a year” for stealing $1 and a book.

In addition to this roster, two other documents I discovered in the State Archives stood out to me. The first was a record of a meeting of the Territory of Hawaiʻi’s Commision of Insanity in 1913. A young Native Hawaiian woman was diagnosed with “mania a potu” and committed to the Insane Asylum. The Insanity Commission's report says: "Her delusion has mainly been that she is related to almost every Hawaiian she sees...She maintained her delusion as to relationship with all Hawaiians in sight." The report also refers to her relatives in quotes. Such an explicit pathologization of Hawaiian kinship and relationality is notable.

The second document was an investigation into the death of a child at Boy’s Industrial School at Waialeʻe. According to children who were interviewed by the deceased child’s mother, the death was due to medical negligence and abuse from staff. According to the deceased child’s friends, he knew he was very sick and begged to be sent to the hospital but he was repeatedly threatened for asking for help with working in the kalo patch (a punishment at the institution) and being placed in solitary confinement in a dark cell. When he fell asleep while working because he was so sick, a staff member poured water on him to wake him up and punish him for not working. He died soon after. The Boy’s Industrial School at Waialeʻe disputed all the claims of the deceased child’s friends and insisted the death was unpreventable.

The mana or power of these stories is undeniable. One of many definitions of mana in the Hawaiian Dictionary is a “hook used in catching eels.” To me, these mo’olelo are hooks that can be used to catch a much larger story.

Hooks can be used not only to catch, but also to secure something in place. At Waiale’e, Kawela shared some of the kaʻao, or Kānaka Maoli mythology, of the place which relates to this function of fishhooks. According to the ka’ao, Waialeʻe is a part of Kahuku Lewa, a landmass once separate from north Oʻahu (Farrant 2020). Waialeʻe is the location of Kalou, one of two inland ponds which mark the location where Kahuku Lewa was attached to Oʻahu (Farrant 2020). One version of this kaʻao credits the kupua (demigod) Māui with fastening Kahuku Lewa to Oʻahu (Farrant 2020). Another version of this kaʻao credits “two old women guardians,” Lāʻieikawai and Malaekahana, with swimming out to Kahuku, fastening wooden fish hooks to either end of the islet, and reeling it back to shore (Farrant 2020). Kawela beautifully interpreted the ka’ao in the context of his work to restore/refasten a traditional fishpond and kalo lo’i to Waiale’e.

The work our collaborators are engaged in on the ʻāina (land, that which feeds) where these institutions once operated is important for many reasons including that the ʻāina holds forgotten/repressed/suppressed memories. As Sydney Iaukea wrote, “Land, body, and memory all inform one another. The land, extending out and into the ocean, holds the practical and epistemological memories of encounters” (2011). I am deeply grateful for the opportunity to participate in this remembering work and meet so many wonderful people engaged in overlapping work.

Kawailoa as an Americanizing Project

Maunawili Training School for Girls opened in 1929 (renamed Kawailoa in 1931), though institutions for girls’ incarceration in Hawaiʻi already existed for decades. From 1929-1950, the institution frequently housed over 100 girls deemed “delinquent,” often for pre-marital sexual activity or living in homes that did not conform to white American standards. Kawailoa, administrators and territorial officials hoped, could turn “delinquent” girls into “good” girls fit for the Hawaiian society the white elite envisioned.

Maunawili Training School for Girls opened in 1929 (renamed Kawailoa in 1931), though institutions for girls’ incarceration in Hawaiʻi already existed for decades. From 1929-1950, the institution frequently housed over 100 girls deemed “delinquent,” often for pre-marital sexual activity or living in homes that did not conform to white American standards. Kawailoa, administrators and territorial officials hoped, could turn “delinquent” girls into “good” girls fit for the Hawaiian society the white elite envisioned. This settler-colonial process of “whitening” the predominantly non-white girls committed to Kawailoa interests me as a student interested in how race and education intersect(ed).

As the Director of the Department of Institutions (the governing board over Kawailoa), Thomas Vance wrote the introduction to the 1945 Kawailoa staff manual. He says the institution’s goals are twofold: “the withdrawal of destructive juveniles from free circulation” and “the rehabilitation of those delinquents.” Removal and rehabilitation, Vance argues, complement each other and can be seen in all aspects of the institution. Contrary to public perception, Vance argues that rehabilitation, rather than removal, is Kawailoa’s central goal; the reformatoryʻs success “means one more good citizen.”

The territorial government's definition of a “bad citizen” was shockingly non-white. In 1940, of the 133 girls at Kawailoa, the staff only labeled one girl as Caucasian. In contrast, 61 girls were listed as Hawaiian or Part Hawaiian. These girls would legally have citizenship status from the Organic Act, though the limits of that citizenship are on full display in the discriminatory incarceration practices. The legal system designated Hawaiians, in this case, Hawaiian girls, as “bad citizens” needing reform at substantially higher rates than white girls.

Aside from their supposed “crimes,” Vance viewed Hawaiians as “bad citizens” based on their labor practices. In his mind, Kawailoa took “wards who have never been taught that work is an important part of every satisfactory life” and taught them to enjoy labor. This argument implies that predominantly non-white girls at Kawailoa did not like or know how to work, which goes against everything we know about settler colonialism and the labor foundations of the US. White hands did very little work on land colonized by the US. Rather, non-white laborers performed manual work while wealthy white people oversaw them. Not only does this erroneous claim ignore the historical setting of non-white labor in Hawaiʻi that planted and harvested all the sugar and pineapple, it also paints non-white Hawaiians as others. It is also worth noting, that while Kawailoa girls performed agricultural work, domestic labor constituted the majority of their duties.

Besides manual labor, Vance is convinced reading is the next best way to rehabilitate girls. He claims that “reading is the number one hobby of the American people,” and therefore one who reads is American. This habit, he continues would “help our wards to acquire a larger vocabulary and fair reading skill,” which reeks all too much of ʻŌlelo Hawaiʻi (Hawaiian language) bans in schools. By 1945, ʻŌleleo had already been pushed out of most schools and many Kanaka children, such as those at Kawailoa, would likely have had English as their first language. Rather than a reflection on the girls’ English literacy, Vance’s argument paints Kawailoa girls as un-American for “committing crimes” rather than reading.

Beyond English literacy skills, enjoying reading was central to rehabilitation. Vance argues that “when a girl has become interested enough in books and magaizines to enjoy staying home to read them, she has made a good start on her rehabilitation.” Here I’m reminded of Vanceʻs claim that successful rehabilitation is indicated by creating a “good citizen.” In this case, a good citizen for a Kanaka girl with minimal political power was one who stayed home. There, women and girls could run white middle-class American-style households and pass down the corresponding cultural values to their children. Good Kawailoa girls produced more “good citizens” Though I often find myself thinking that release from these institutions was the end of their “withdrawal..from free circulation,” Vance indicates that successful “rehabilitation” continued keeping girls out of the public sphere.

Kawailoa’s goals of removal and rehabilitation, then, did not end when the girls completed their sentence. The curriculum was designed to stay with them throughout their lives, making them “good citizens, wives and mothers” as they passed American messages along to friends, family, and especially their children. “Successful rehabilitation” was intergenerational.

Updates from Summer 2023

Sharing histories with Secretary Deb Haaland and my Auntie Georgie

Maile here, with a number of updates from this past summer!

First, you may notice some new names and faces associated with this project. See all new additions on our Team page, and stay tuned for more on this blog from our other researchers.

During the summer of 2023, I had the opportunity spend a few weeks in Hawaiʻi, conducting archival research at the Hawaiʻi State Archives, as well as visiting with community folks who have significant ties or expertise related to the history of reformatory and training schools in Hawaiʻi. Several of those folks have graciously agreed to be on a community advisory board that will assist in strengthening public engagement with this history and building a website that provides more access to historical documents about these schools. Our board members are also listed on our Team page, and we will add more information about them shortly.

Two undergraduate students researchers, Eliana Massey and Callie Avondet, from the University of Utah were able to join me for a week in Hawaiʻi to assist with this research. You will hear directly from them soon about their experiences, and we will share more about the results of our research on the blog over the next few months.

We also had the opportunity to connect with Dr. Derek Taira, in the College of Education at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, who is coming on board to help build a website about the history of the reformatory and training schools. Dr. Taira has valuable experience building websites: check out his existing website Imua, Me Ka Hopo Ole, Forward Without Fear: Understanding the Native Hawaiian experience during the territorial period (1900-1959).

One highlight from the summer for me was participating in an event at Kawailoa on June 26th, where the U.S. Secretary of the Interior, Deb Haaland, visited Hawaiʻi as part of her “Road to Healing” tour. This tour was in response to the federal report on Indian boarding schools, released in May 2022, which included several institutions in Hawaiʻi. Mark Kāwika Patterson, warden of the Kawailoa Youth and Family Wellness Center, invited me to come speak briefly about the history of Kawailoa and other similar institutions in Hawaiʻi to provide some historical context for understanding the similarities and differences with boarding schools in the Native American context. It was a great honor to present in front of Secretary Haaland, as well as many important leaders from our Native Hawaiian community. My auntie Georgie Awo (pictured with myself and Secretary Haaland below) was also there, and shared her own experiences of coming to Kawailoa as a child when her mother (my tūtū) worked there as well as visiting later when she was a social work student. Secretary Haaland seemed moved by the stories folks in the audience shared with her.

This semester, Eliana, Callie and I continue to work on organizing and analyzing archival materials we collected from the Hawaiʻi State Archives. Derek and I are beginning to draft proposals for a few grants that could support further community engagement and a digital database related to these histories. Avis (one of our community advisory board members), Eliana and I plan to attend the Association of Tribal Archives, Libraries and Museums conference next month as a way to better understand how other Indigenous communities create meaningful public and digital history projects on similar topics. In the spring, Derek and I will present some of our research at the Organization of American Historians conference.

There is much more to say about all I have learned over the past few months about this history - our team hopes to provide more regular updates and reflections on this blog over the next few months. Mahalo for reading!

At Kawailoa with Secretary Haaland and Auntie Georgie

Share your moʻolelo about Kawailoa, Koʻolau, Waialeʻe or Waimano

Share your moʻolelo (story) of training schools in Hawaiʻi from the 1940s-1970s.

In addition to archival research, I am actively seeking out folks with experience of these institutions from around the 1940s-1970s to conduct interviews with. The interviews will become part of an oral history archive about these schools.

What is oral history?

Oral history supplements “official” archival materials by offering more personal insights into how people lived and experienced certain events in the past. They generally consist of written transcripts of open-ended interviews conducted by a researcher with a person who has particular experiences of some event or historical period. In general, oral history interviews are not anonymous; participants agree to have their real name used with the records of their interview. Oral history is important especially for Native Hawaiians and other communities of color because the official archives often do not reflect the experiences of regular people.

What can I expect if I agree to participate in this oral history project?

Before we record an interview, we will touch base about expectations and scheduling. Before the interview is conducted, I will share informed consent and copyright documents that explain how the transcripts will be used. Interviews can be conducted in person or online over Zoom. They usually last 1.5-3 hours. The oral history interviews for this project are wide-ranging and ask participants to share about their own backgrounds and family as well as more about whatever experience they had with Kawailoa, Koʻolau, Waialeʻe, Waimano, or other institutions. After the interview, which will be recorded, a written transcript is created and edited for clarity and errors. After the participant reviews the transcript, with their permission, the transcript and audio/video of the interview becomes part of a public archive. The Center for Oral History at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa will eventually house the interviews from this project. Scholars and other community members will be able to access the transcripts online.

Your stories, your moʻolelo, are important and precious. If you are willing to share yours, please contact me: maile.arvin@utah.edu.

Undergraduate research opportunity, apply by Jan 29, 2023

10 week summer fellowship opportunity for undergraduate researchers

If you are interested in this research, and are an undergraduate student (from any US university or college), you can apply to work with me over the summer of 2023, through the Summer Program for Undergraduate Research at the University of Utah. Read more about the opportunity through the links below.

SPUR is a nationally competitive opportunity that provides undergraduate students with an intensive 10-week summer research experience under the mentorship of a University of Utah faculty member. The program provides opportunities to gain research experience in a variety of disciplines.

SPUR applications are due Jan 29, 2023.

Details on specifically applying to work with me on Nā Lei Poina ʻOle here.

The overall goal of the project is to provide further public engagement with this history of government institutions that forcibly took in children in Hawaiʻi. Accordingly, the work involves archival research, oral history interviews, building a website with digitized resources like story maps, and community engagement. The SPUR student will work closely with Dr. Arvin to identify the areas of this work that they are particularly interested in or suited to, and Dr. Arvin will shape the specific tasks for the student accordingly. However, in general, the student will conduct research on (1) the histories of the sites where these institutions were, looking for traditional land use, moʻolelo (traditional stories/legends related to the area), and the meaning of the place names around the schools; (2) digitized newspaper accounts related to the histories of these institutions - in English and/or in Hawaiian language if the student has Hawaiian language expertise; (3) establishing similarities and differences between these institutions in Hawaiʻi and the boarding schools in the Native American contexts and (4) developing a website to share the results of this research and provide some interpretation of the sources they find for a general, public audience.

This work is important and timely…. The student will gain hands-on skills with conducting original research, analyzing primary and secondary documents, forming their own arguments based on historical evidence, and writing about this history for the public. The student will also be immersed in Hawaiian history and Indigenous Studies scholarship, and be able to connect with our growing U of U community of faculty and students in Pacific Islands Studies.

Did Hawaiʻi have Native boarding schools?

The inclusion of institutions from Hawaiʻi in a new report on colonial boarding schools raises important questions.

The following is an excerpt from an op-ed I wrote back in May 2022, following the release of a report by the US Federal Department of Interior about the histories and legacies of boarding schools. A number of the institutions I am researching were named in this report, much to my surprise. I continue to grapple with how to understand, and appropriately contextualize, the inclusion of Hawaiʻi in this report.

On May 11, the Department of Interior released a Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative investigative report, the first official accounting of the hundreds of federally supported institutions that, for generations, worked to culturally assimilate Indigenous children to white American norms.

The report identifies seven institutions from Hawaii as fitting the criteria to be considered boarding schools. This is surprising because neither scholars nor many Native Hawaiians have historically viewed these schools as part of the same system as Indian boarding schools.

Hawaii’s inclusion in the report is complicated in a number of ways. For one, it raises long-standing debates over federal recognition of Native Hawaiians, who have a different, less established legal and political status than federally recognized Native American tribes with tribal governments.

Many Native Hawaiians do not see the Department of Interior as having appropriate jurisdiction over Hawaiian affairs; many believe in pushing for a full restoration of independence from the United States. The report also noticeably makes some significant errors in reference to Hawaii — such as designating one school as located at “Kawailou.” There is no such place as “Kawailou.” This is likely a misrecognition of an actual place, Kawailoa. Further, it is unclear to what extent, or who, among the Hawaiian community, was consulted in the writing of the report.

Despite such issues, the report might be an occasion for Native Hawaiians and the public more broadly to learn more and grapple together with the legacies of the institutionalization of Hawaiian children in the late 19th and early to mid-20th centuries. This history in Hawaii bears both striking similarities as well as significant differences from Native American contexts.

You can read the rest of this essay here: https://truthout.org/articles/native-hawaiians-are-confronting-the-legacies-of-indian-boarding-schools/