Moʻolelo as Resistance at Kawailoa Industrial School for Girls

A long-distance view of Kawailoa Industrial School for Girls from a 1940’s institutional scrapbook. Digitally colorized.

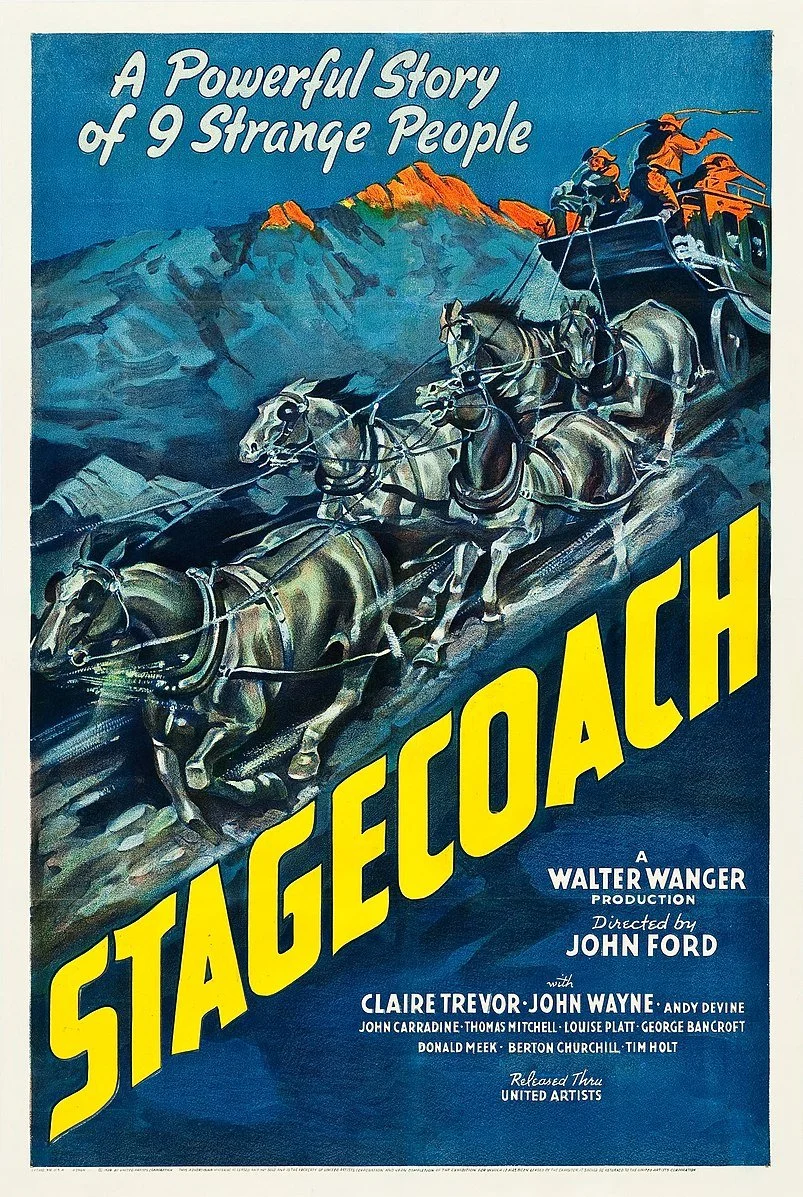

The teenage girls who were incarcerated at Kawailoa Industrial School were not too different from teenage girls today. They enjoyed watching action-packed movies, staying up to date on the love lives of their favorite celebrities, and talking about their crushes and “first times.” In 1939, adventure stood out as the favorite movie genre among the majority (57%) of girls living at Kawailoa Industrial School, as indicated by a survey with 65 responses. The 1939 cinematic landscape included The Wizard of Oz, which continues to enchant viewers with its timeless melody "Somewhere Over the Rainbow," Stagecoach, starring John Wayne in his breakthrough role, and The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes, which was the last Sherlock Holmes film set in the Victorian period. Out of the Western, mystery, and crime subgenres, the girls preferred westerns and mysteries.

While it is difficult to know exactly how incarceration at Kawailoa Industrial School affected the girls' preferences, we can speculate that the boredom and drudgery of confinement might have fed their love for adventure films.

Softening into fictional worlds where “troubles melt like lemon drops” likely offered some solace to girls who missed their loved ones.

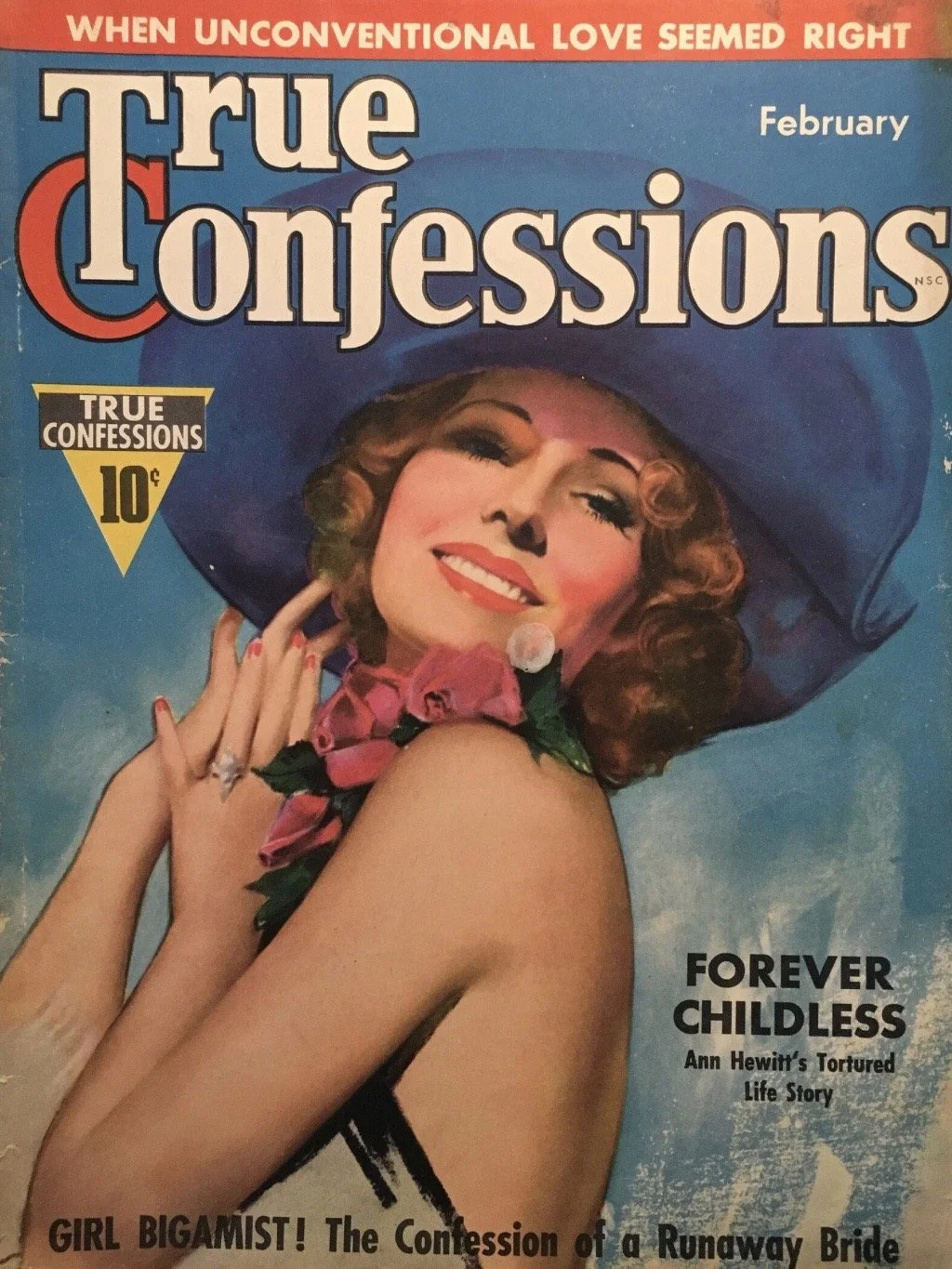

The previously mentioned 1939 survey also found that romance was the favorite written genre of the largest percentage of girls (48%) living at Kawailoa Industrial School. In particular, the girls liked reading the popular magazines True Confessions and Screen Stories. These magazines probably offered not just entertainment but also a feeling of normalcy for teenage girls, many of whom were 18 or older, who were deprived of normal opportunities to explore romance and sexuality. At least some girls also viewed magazines like these as sources of sexual information. When asked about their sexual education sources, 13% of 36 respondents mentioned books and magazines.

Another 20% of girls at Kawailoa Industrial School in 1939 stated that they had no sexual education. Determining whether social taboos surrounding sex may have influenced this response is challenging. However, it is clear that many girls at Kawailoa Industrial School were lacking substantial information regarding sex and likely held inaccurate beliefs.

While many other girls in Hawaiʻi during this era also received inadequate sexual education, they were fortunate to at least have access to guidance from their mothers and aunties. In contrast, girls at Kawailoa Industrial School had very limited opportunities to interact with their mothers and aunties. This exacerbated their sexual vulnerability.

Girls at Kawailoa Industrial School turned to each other for sexual information, with 18% of survey respondents indicating that their female friends were their first sources of sexual knowledge.

“It is common practice for girls, who have run away and have been apprehended, to be returned to their respective cottages where they entertain the other girls with tales of their escapades and conquests while on “leave.” Their sex experiences are the choice bits of entertainment.”

While the author of the article quoted above included these details as evidence of the supposed inadequacy of moral training at Kawailoa Industrial School, these habits can also be interpreted as a strategy employed by the teenage girls to address their lack of sexual education. The storytelling sessions following escapes allowed girls to share information with each other about their bodies and the world beyond the confines of the institution.

While escapes posed a direct challenge to the institution's control, “talking story" after recapture might be seen as an equally significant form of resistance.

Moreover, these talk story sessions likely motivated further escapes which surely led to more storytelling gatherings, thus reinforcing a unique moʻolelo-based cycle of resistance.

Mo’olelo, which is often translated into English as “story,” is composed of the words moʻo (a series of events such as the repeated shedding of a lizard’s skin) and ʻōlelo (language or spoken words).

Moʻo is a particularly helpful word for describing these post-escape (and pre-new-escapes!) talk story gatherings. Given the sheer quantity and frequency of escapes, these moʻolelo-sharing events were likely repeated on a weekly basis.

Photo by Egor Kamelev

The “tales” of their friends’ “escapades and conquests” undoubtedly brought much pleasure to the girls’ adventure-loving hearts. Unfortunately, this practice also touches on one of the darkest sides of life for girls incarcerated at Kawailoa Industrial School.

“The girls who work as prostitutes and are sent to the school tell other girls the names and addresses of solicitors who are always willing to harbor an escaped girl. It is not incidental that the girls are enlisted into the ranks of prostitution for the privilege of staying out of the hands of the police.”

This quotation offers a small glimpse into the difficult decisions girls faced as a result of the carceral system. Freedom remained elusive regardless of what choices a girl made under these circumstances.

While the pleasure of watching, reading, sharing, and listening to stories did not negate this reality, it empowered these girls to experiment with freedom.