We, the Women: Public Perceptions of Juvenile Delinquency in the 1950s

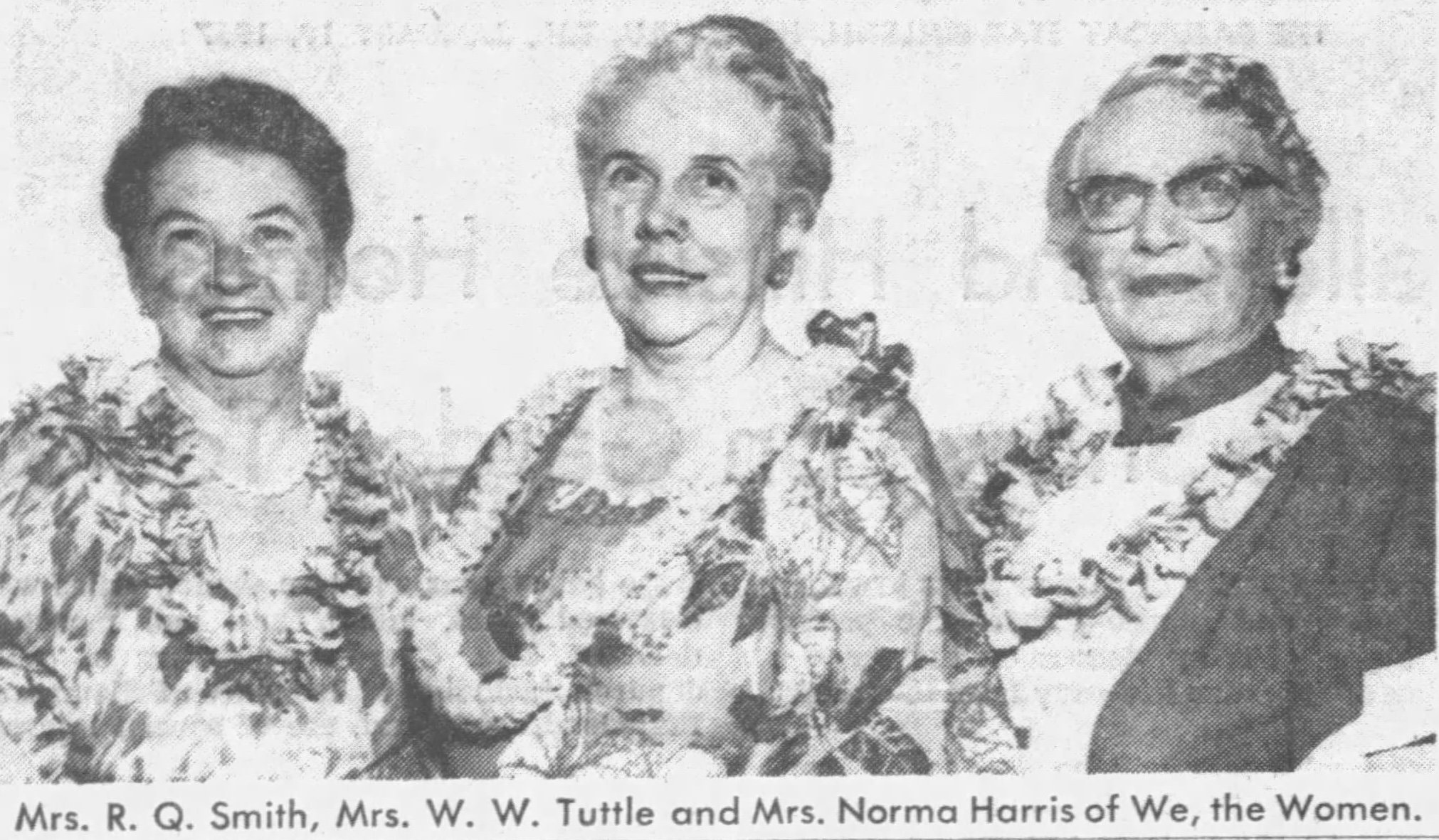

Despite his popularity, Elvis can’t explain all the public concern about juvenile delinquency in Hawaiʻi during 1957. Organizations such as We, the Women had brought juvenile delinquency to the forefront of public awareness since the early 1950s. We, the Women was a conservative women’s group in Hawaiʻi born to protest an impending public utilities worker strike in 1946.

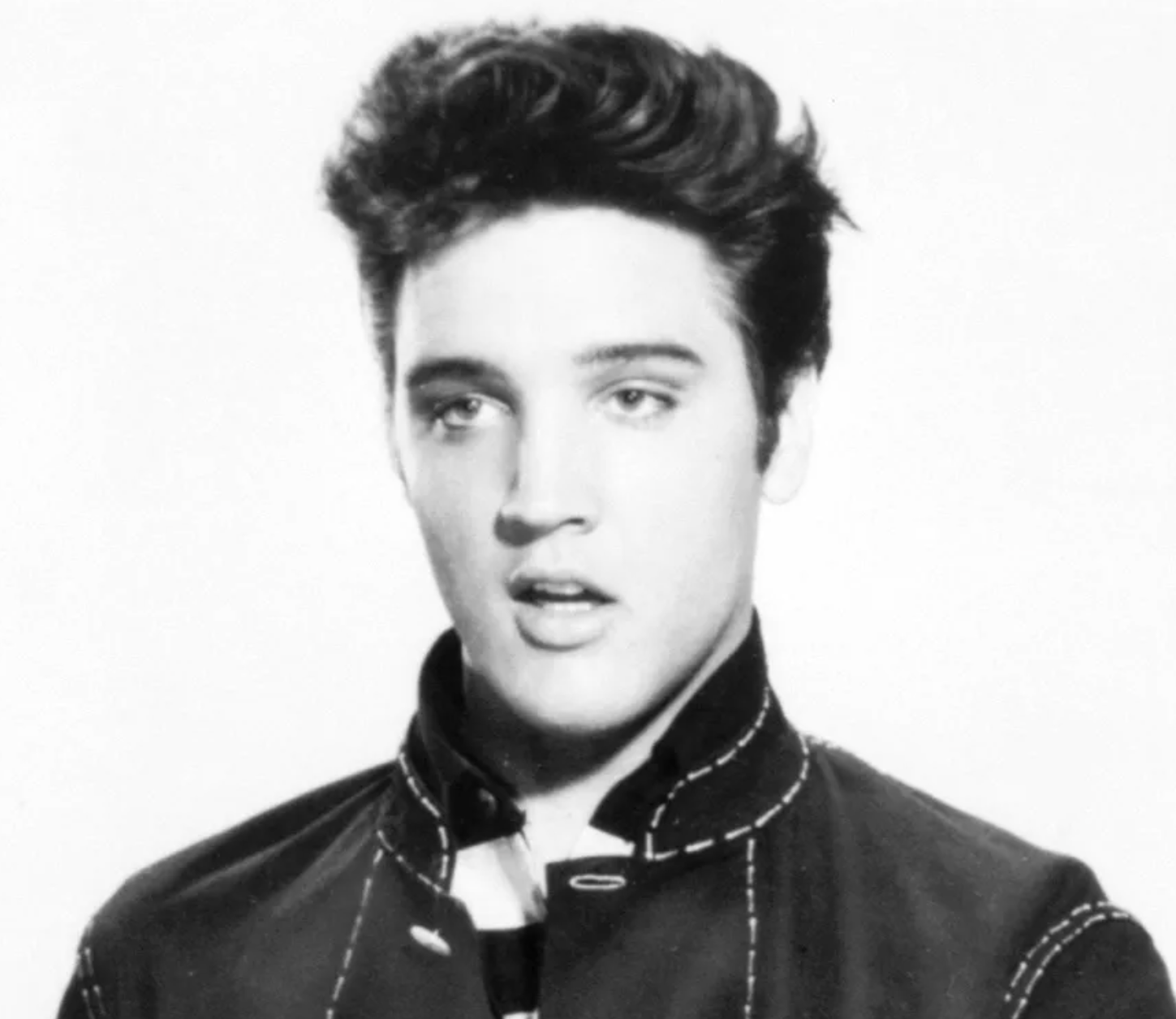

In 1957, Hawaiʻi residents hotly debated Elvis Presley’s dance moves. The Honolulu Star-Bulletin reported “receiving far more letters for and against Elvis Presley than we can possibly publish.”[1] Eunice Kiyuna, a 13 year old living on Hawaiʻi was one of the few who successfully got her letter in the paper, arguing that she “didn’t see anything wrong with his singing or his style of shaking.”[2]

The public also critiqued other aspects of Elvis. In addition to his dancing, Elvis’ “haircut that doesn’t look like a haircut" garnered public attention.[3] The length and volume all marked his unique hairstyle and brand.

Some people, however, associated Elvis’ brand, including his haircut, with juvenile delinquency. Rather, teenage boys having such an “extreme coiffure” was a “badge of delinquency” that would almost certainly signify the boy would soon be following Elvis’ footsteps towards arrests.

Despite his popularity, Elvis can’t explain all the public concern about juvenile delinquency in Hawaiʻi during 1957. Organizations such as We, the Women had brought juvenile delinquency to the forefront of public awareness since the early 1950s.

We, the Women was a conservative women’s group in Hawaiʻi born to protest an impending public utilities worker strike in 1946. They claimed to represent “thousands of other women in the Territory,” and reported 300 women showing up to their meeting that approved a letter to the governor asking him questions such as, “What do you plan to do to make it forever impossible for a minority group to put its selfish interest above the general welfare to the extreme extent of shutting off utilities?” and pushing back on the lack of prosecutions against previous strikers.[4] When August 1st came around, the day the strike was planned to begin, the Honolulu Star-Bulletin instead circulated Letters from Readers about how to prevent “the threatened and perhaps still pending strike” from happening and praising We, the Women for organizing.[5]

“‘We, the Women of Hawaii’ (God bless ‘em), have now arrived.”

In the early 1950s, We, the Women organized around legislative changes. They hosted luncheons to discuss issues such as fluoridating water, sales taxes, and juvenile delinquency. We, the Women, a juvenile court judge, and other officials believed that the best way to prevent juvenile delinquency was through education reform. We, the Women supported a platform that increased the number of remedial education teachers, vocational education classes, and “required courses in family living in intermediate and high school levels.”[6]

Their early efforts failed to curb juvenile delinquency and when We, the Women took up juvenile delinquency again in 1957, they prioritized community action rather than pressure on the legislature. The agenda consisted of three main components: “Cause and treatment of youthful crime,” “Study of existing criminal code and penalties for ‘offenses against the person’ and offenses against property,” and “The rights of the citizen to protect himself and his property.” This agenda marked a stark difference from their focus on prevention in the early 1950s. Instead, We, the Women prioritized understanding the law and protecting themselves and their property. Their self-interest in juvenile delinquency rather than public or youth interest took precedence by 1957.

“Federal officials testify on juvenile delinquency. It’s a nonpartisan problem. Each party is convinced the other one proves what happens to juvenile delinquents.”

Juvenile delinquency was in the forefront of public concern and We, the Women wanted to expand the number of people and groups involved in tackling it. In addition to the eight women’s groups already working with them, We, the Women invited over 200 other groups on Oʻahu to join their task force.[7] Not only did We, the Women’s status and recognition on the island help bring attention to juvenile delinquency, it was already a large enough issue to garner so much public support and attention.

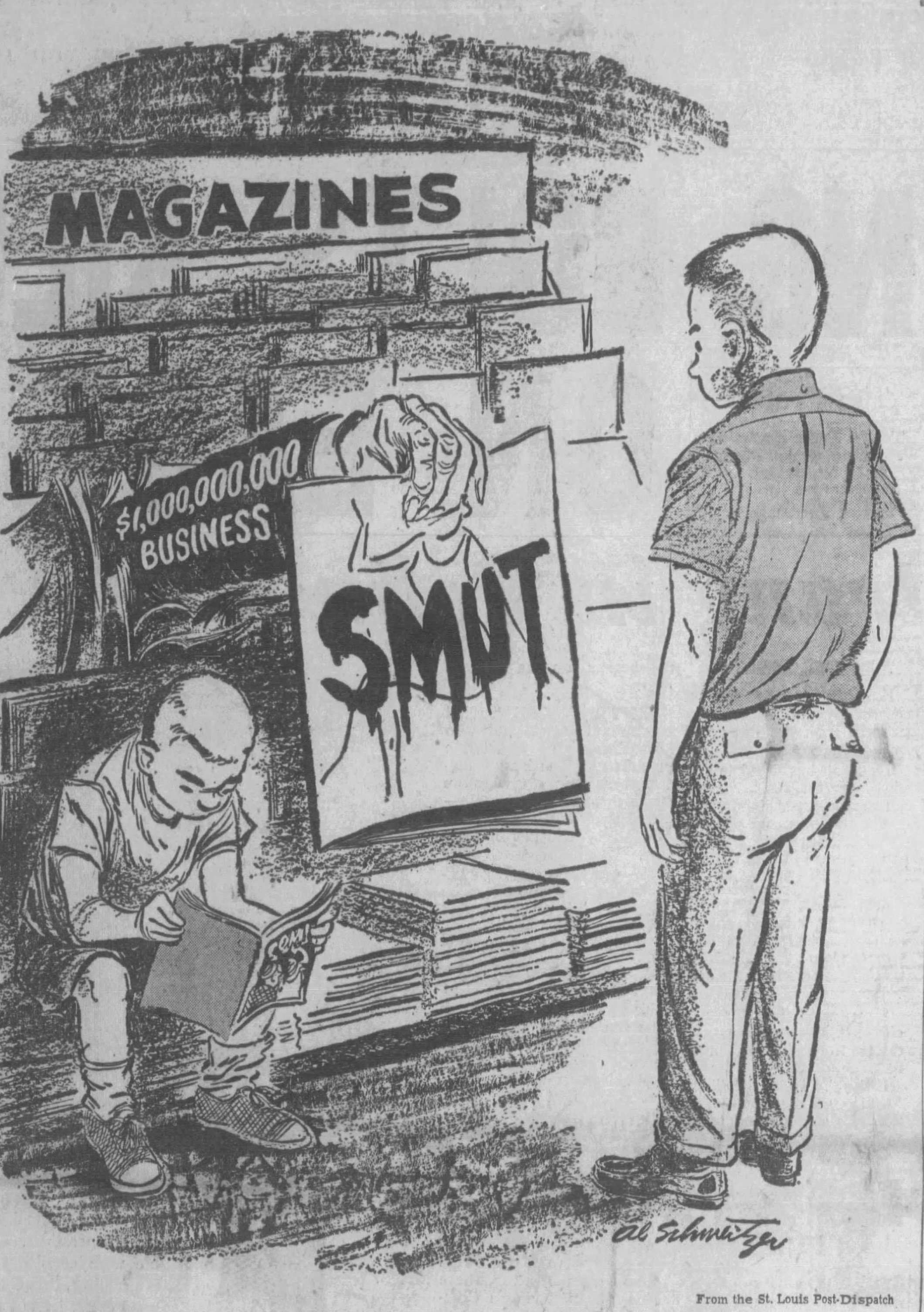

By late 1957, We, the Women’s campaign created the Community Crime Council. Strangely, the first 6 person board did not include a representative from We, the Women, but largely adopted their proposed agenda. Mrs. Kellerman, of We, the Women, credited as a key force in creating the council, and We, the Women was likely one organization who partnered with the council from the beginning. Council members spoke at public events and conducted community research to raise public consciousness about juvenile delinquency and what they believed were its causes, such as “smut” literature.[8]

We, the Women’s work throughout the 1950s reflected and amplified concerns about juvenile delinquency by organizing people against the perceived threat. Examining their role and public conversations around Elvis Presley help us understand how threatening the public found juvenile delinquency, and commonplace its causes.

[1] Eunice Kiyuna, “Letters from Readers,” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, February 12, 1957.

[2] Kiyuna.

[3] Elvis Presley as quoted in Wayne Harada, “Music,” Honolulu Advertiser, November 17, 1957.

[4] Mona H. Holmes et al., “Why No Action, Stainback Asked,” Honolulu Advertiser, July 25, 1946, https://www.newspapers.com/image/259267916/?terms=%22We%2C%20the%20Women%22&match=1.

[5] ONE OF THEM, “Letters from Readers,” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, August 1, 1946, https://www.newspapers.com/image/258514487/?terms=Public%20utilities%20strike&match=1.

[6] “Women Indorse Program on Juvenile Delinquency,” The Honolulu Advertiser, March 12, 1953.

[7] Fletcher Knebel, “Potomac Fever,” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, November 27, 1953, https://www.newspapers.com/image/258863501/?match=1&terms=%22Potomac%20Fever%22%20.

[8] “200 Clubs Asked to Join Juvenile Delinquency Fight,” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, September 25, 1957.

[9]“City Crime Rate Increases Among Those Under 25,” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, November 16, 1957; “Council Formed to Fight Crime Among Juveniles,” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, October 31, 1957; “Smut Literature Available to Teenagers in Hawaii,” The Honolulu Advertiser, August 30, 1959.

Kawailoa as an Americanizing Project

Maunawili Training School for Girls opened in 1929 (renamed Kawailoa in 1931), though institutions for girls’ incarceration in Hawaiʻi already existed for decades. From 1929-1950, the institution frequently housed over 100 girls deemed “delinquent,” often for pre-marital sexual activity or living in homes that did not conform to white American standards. Kawailoa, administrators and territorial officials hoped, could turn “delinquent” girls into “good” girls fit for the Hawaiian society the white elite envisioned.

Maunawili Training School for Girls opened in 1929 (renamed Kawailoa in 1931), though institutions for girls’ incarceration in Hawaiʻi already existed for decades. From 1929-1950, the institution frequently housed over 100 girls deemed “delinquent,” often for pre-marital sexual activity or living in homes that did not conform to white American standards. Kawailoa, administrators and territorial officials hoped, could turn “delinquent” girls into “good” girls fit for the Hawaiian society the white elite envisioned. This settler-colonial process of “whitening” the predominantly non-white girls committed to Kawailoa interests me as a student interested in how race and education intersect(ed).

As the Director of the Department of Institutions (the governing board over Kawailoa), Thomas Vance wrote the introduction to the 1945 Kawailoa staff manual. He says the institution’s goals are twofold: “the withdrawal of destructive juveniles from free circulation” and “the rehabilitation of those delinquents.” Removal and rehabilitation, Vance argues, complement each other and can be seen in all aspects of the institution. Contrary to public perception, Vance argues that rehabilitation, rather than removal, is Kawailoa’s central goal; the reformatoryʻs success “means one more good citizen.”

The territorial government's definition of a “bad citizen” was shockingly non-white. In 1940, of the 133 girls at Kawailoa, the staff only labeled one girl as Caucasian. In contrast, 61 girls were listed as Hawaiian or Part Hawaiian. These girls would legally have citizenship status from the Organic Act, though the limits of that citizenship are on full display in the discriminatory incarceration practices. The legal system designated Hawaiians, in this case, Hawaiian girls, as “bad citizens” needing reform at substantially higher rates than white girls.

Aside from their supposed “crimes,” Vance viewed Hawaiians as “bad citizens” based on their labor practices. In his mind, Kawailoa took “wards who have never been taught that work is an important part of every satisfactory life” and taught them to enjoy labor. This argument implies that predominantly non-white girls at Kawailoa did not like or know how to work, which goes against everything we know about settler colonialism and the labor foundations of the US. White hands did very little work on land colonized by the US. Rather, non-white laborers performed manual work while wealthy white people oversaw them. Not only does this erroneous claim ignore the historical setting of non-white labor in Hawaiʻi that planted and harvested all the sugar and pineapple, it also paints non-white Hawaiians as others. It is also worth noting, that while Kawailoa girls performed agricultural work, domestic labor constituted the majority of their duties.

Besides manual labor, Vance is convinced reading is the next best way to rehabilitate girls. He claims that “reading is the number one hobby of the American people,” and therefore one who reads is American. This habit, he continues would “help our wards to acquire a larger vocabulary and fair reading skill,” which reeks all too much of ʻŌlelo Hawaiʻi (Hawaiian language) bans in schools. By 1945, ʻŌleleo had already been pushed out of most schools and many Kanaka children, such as those at Kawailoa, would likely have had English as their first language. Rather than a reflection on the girls’ English literacy, Vance’s argument paints Kawailoa girls as un-American for “committing crimes” rather than reading.

Beyond English literacy skills, enjoying reading was central to rehabilitation. Vance argues that “when a girl has become interested enough in books and magaizines to enjoy staying home to read them, she has made a good start on her rehabilitation.” Here I’m reminded of Vanceʻs claim that successful rehabilitation is indicated by creating a “good citizen.” In this case, a good citizen for a Kanaka girl with minimal political power was one who stayed home. There, women and girls could run white middle-class American-style households and pass down the corresponding cultural values to their children. Good Kawailoa girls produced more “good citizens” Though I often find myself thinking that release from these institutions was the end of their “withdrawal..from free circulation,” Vance indicates that successful “rehabilitation” continued keeping girls out of the public sphere.

Kawailoa’s goals of removal and rehabilitation, then, did not end when the girls completed their sentence. The curriculum was designed to stay with them throughout their lives, making them “good citizens, wives and mothers” as they passed American messages along to friends, family, and especially their children. “Successful rehabilitation” was intergenerational.